Rock Azalea

えだしあればおひぞしにけるいはつつじはなさくまでにならむとやみし

| eda shi areba oi zo shinikeru iwatsutsuji hana saku made ni naramu to ya mishi | There the branches are, so Growing seem to be Azaleas on the rocks— Until the flowers bloom Here I’ll be, I saw. |

10

Peach Blossom

さきし時なほこそみしかももの花ちればをしくぞ思ひなりぬる

| sakishi toki nao koso mishika momo no hana chireba oshiku zo omoinarinuru | When they bloomed, Did I gaze upon Peach blossoms, and When they scattered, regret I felt deeply, indeed! |

9[i]

[ii] This poem is included in Shūishū (XVI: 1030) as an anonymous poem with the headnote ‘Topic unknown’.

Pear Blossom

春立てばいづこともなしのはなりぬわかなつむべくなりぞしにける

| haru tateba izuko tomo nashi no hanarinu wakana tsumubeku nari zo shininkeru | When the springtime comes, There’s nowhere that’s Not far away, for I should pick fresh herbs— That’s what I’ve decided! |

8

This poem is an acrostic, with ‘pear blossom’ (nashi no hana) contained within nashi no hanarinu.

Garden Cherry

あさごとに我がはくやどのにはざくらはなちるほどはてもふれでみむ

| asa goto ni wa ga haku yado no niwazakura hana chiru hodo wa te mo furede mimu | Every single morning Around my house I could sweep Garden cherry Blossoms, scattered I’ll not touch them, but gaze on them, instead! |

7[i]

[i] This poem is included in Shūishū (I: 61) as an anonymous poem with the headnote ‘Among the poems from a poetry match held by the Fujitsubo Junior Consort during the reign of the Engi Emperor’, and also in Kokin rokujō (4234) with the headnote ‘Garden Cherry’.

Taiwan Cherry

あづさゆみ春の山べにけぶりたちもゆともみえぬひざくらのはな

| azusayumi haru no yamabe ni keburi tachi moyu tomo mienu hizakura no hana | A catalpa bow: From the mountainside in springtime Smoke rising— Doesn’t it appear to be burning with Fiery cherry blossoms. |

6[i]

The Japanese name for this breed of cherry is hizakura (‘fire cherry’)—hence the imagery used in the poem.

[i] This poem is included in Kokin rokujō (4234), attributed to Ōchikōchi no Mitsune with the headnote ‘Taiwan Cherry’.

Round One

Left (T – Win)

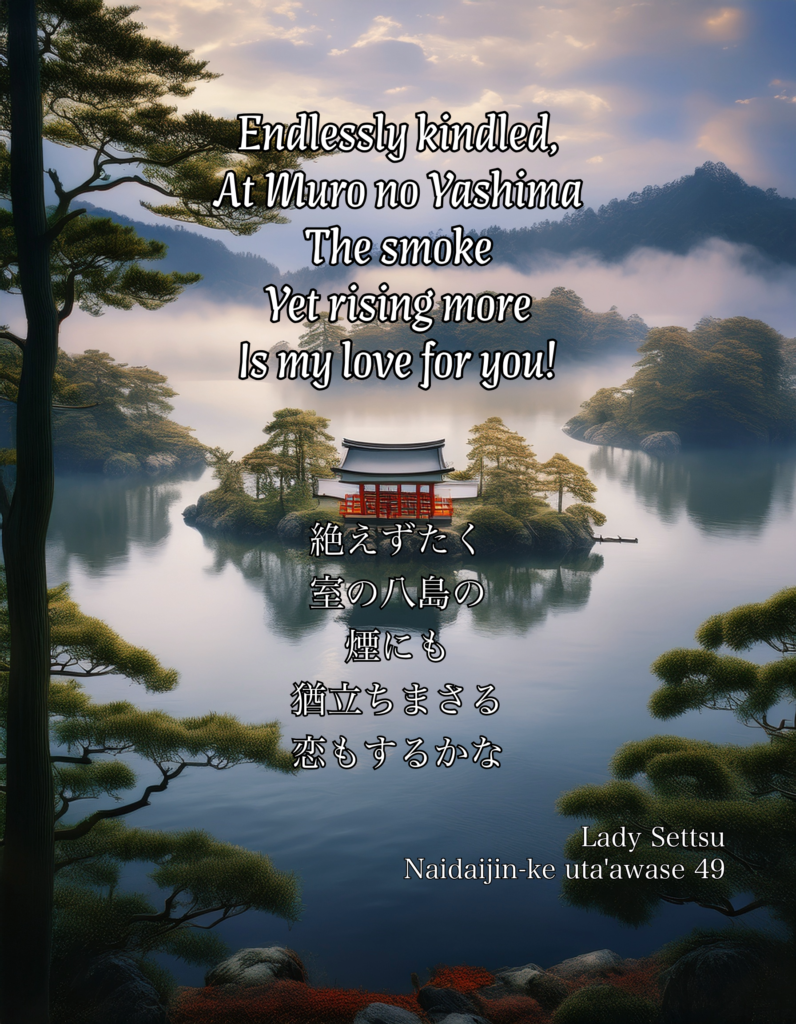

絶えずたく室の八島の煙にも猶立ちまさる恋もするかな

| taezu taku muro no yashima no keburi ni mo nao tachimasaru koi mo suru kana | Endlessly kindled, At Muro no Yashima The smoke Yet rising more Is my love for you! |

Lady Settsu

49

Right (M – Win)

杯のしひてあひみむとおもへども恋しきことのさむるよもなき

| sakazuki no shiite aimimu to omoedomo koishiki koto no samuru yo mo naki | Over a cup of wine To press you to meet I thought, yet My love for you Will never cool in this world! |

Lord Akikuni

50

Toshiyori states: the first poem’s ‘endlessly kindled’ is an error. Fires are not actually kindled at Muro no Yashima—vapour rising from clear waters in the land appears to be smoke, so I wonder about the use of ‘kindled’ in this context. Nevertheless, if one was referring to real smoke, why wouldn’t you compose in this way? The tone of the poem isn’t bad. The second poem is an interesting display of technique, but it doesn’t appear that one would have to compose like this. Saying ‘cup’ leads to ‘wine’ and emphasises the drinking of it, but then if there were no wine and no drinking, how could one press someone to do something? In addition, I wonder whether it’s appropriate to begin with ‘cup’? This is an excess of technique over substance. The Left is more poetic, so I say it’s the winner.

Mototoshi states: what are we to make of ‘Endlessly kindled, / At Muro no Yashima / The smoke’? And what do the fires kindled at this location resemble? There are two senses of ‘Muro no Yashima’: one is a location in Shimotsuke; the second refers to people’s dwellings—we know from earlier treatises that forges are described as ‘Muro’. Which of these two senses is being used here? Whichever it is, ‘endlessly’ does not appear to have been previously associated with either of them. For example, there’s Koreshige’s poem:

風ふけば室のやしまの夕煙心のうちに立ちにけるかな

| kaze fukeba muro no yashima no yūkeburi kokoro no uchi ni tachinikeru kana | When the wind blows Across Muro no Yashima At eventide as smoke, Within my heart, My passion soars… |

It does not appear that the smoke rises endlessly here. Exemplars of endlessly rising smoke are the peak of Asama, or Mount Fuji, and these seem to have long been the subject of compositions. It seeming that this poem sought to express the essential meaning of ‘endlessly kindled’, such enquiries need to be made and, if I may be so bold, do not appear, do they? The Right’s poem has ‘Over a cup of wine / To press you to meet / I thought, yet’—while the conception of ‘press’ here sounds extremely unusual, what does it mean that ‘My love for you / Will never cool in this world’? It seems that ‘cool’ as a piece of diction is being used to make drunkenness a metaphor for being in love. If that’s the case, then, well, there are many foundational texts on this. So, even if one gets drunk, what then happens? Is there a world where this never ‘cools’? There was the case of man in Cathay who spent a thousand nights drunk, but that was only three years and not without end. In the sutras there is the drunkenness of ignorance and that might be a world in which one would not find sobriety, but there is no way to make this applicable in this poem. It is a little better than the Left poem’s endless kindling and extremely charming.

Round Twelve

Left

霜枯に移ひ残る村菊はみる朝ごとにめづらしきかな

| shimogare ni utsuroinokoru muragiku wa miru asa goto ni mezurashiki kana | Burned by frost, Faded and lingering A cluster of chrysanthemums When I see them every morn Strikes me afresh! |

Lord Toshitaka

47

Right (Both Judges – Win)

置くしものなからましかば菊のはな移ふ色をけふみましやは

| oku shimo no nakaramashikaba kiku no hana utsurou iro o kyō mimashi ya wa | Fallen frost Were there none, then Chrysanthemum blooms Faded hues I would not see today… |

Lord Tamezane

48

Toshiyori states: the first poem has nothing remarkable about it, apart from the undesirable use of ‘clustered chrysanthemums’. The second poem’s sense could be that when the frost has fallen, the chrysanthemum won’t display faded hues, but it is a mistake to link frost fall and being able to see them. However, if we interpret is as meaning it has fallen, so we can then view them for a long time, well, I can understand that, and will make it the winner.

Mototoshi states: this poem has no faults, but it does not appear to be a poem suited to a poetry match—it’s just rather dull. The poem of the Right, too, lacks anything worth pointing out and just says that the poet wants to gaze upon faded hues today—this seems a bit cliched, but I’d say it’s superior.